Vanessa Edwige, Joanna Alexi, Belle Selkirk, Pat Dudgeon

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have thrived in Australia for more than 60,000 years and are among the oldest continuing cultures worldwide. In this time, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander relational ways of being, knowing and doing kept families and communities well and ensured their continual survival for thousands of generations.

Due to the devastating impacts of colonisation, and resultant social inequities, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s health and wellbeing are significantly lower than other Australians.

Compared to other Australians, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are almost three times more likely to experience high psychological distress, twice as likely to be hospitalised for a mental health condition, and twice as likely to die by suicide. For young people, this rate is even higher.

System changes and Indigenous paradigms of wellbeing represent a clear path forward to address the disproportionate mental health risks experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

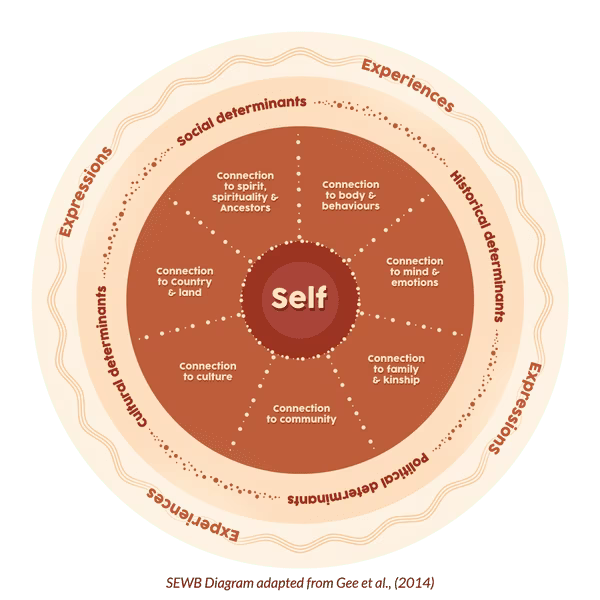

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, wellbeing is viewed holistically, described as social and emotional wellbeing (SEWB). SEWB considers mental health as inseparable from one’s physical health, and one’s connections to family, community, Country, culture, and spirituality. These domains are interlinked and each is equally integral to bringing about the total wellbeing of an individual and their community.

SEWB also considers the context in which people live and grow. This includes historical and political determinants of health, such as the impact of colonisation; and social and cultural determinants, including experiences of racism, poverty, inadequate access to water, food, housing, and healthcare; and protective determinants, such as cultural revitalisation.

Adapted from Gee, G., Dudgeon, P., Schultz, C., Hart, A., & Kelly, K. (2014). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social and Emotional Wellbeing. In P. Dudgeon, H. Milroy, & R. Walker (Eds.), Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice (2nd ed.).

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander scholars, practitioners and communities articulate the importance of SEWB to improving the wellbeing of Indigenous people. However, mental health systems in Australia were established on western conceptions of wellbeing and the disease-deficit model, which failed to acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander practices of holistic wellbeing. These perspectives are reinforced by education systems, which have taught little about SEWB.

Having Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander psychologists and culturally responsive clinicians are imperative to optimising culturally safe mental health care. Despite this, fewer than 1% of psychologists identify as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander, substantially below population estimates (3.3%). Addressing this underrepresentation must be at the forefront of considerations if we are to meet the identified needs of people and communities.

The Australian Indigenous Psychologists Association (AIPA) is committed to achieving equitable participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples within the psychology profession in Australia.

Where do we go from here?

Decolonising the mental health system is key to transformative system change and is a movement that has been gaining significant traction in recent years. It is a movement that seeks to restore harmony to the knowledge taught and practised, to the benefits of all Australians.

Decolonising the mental health system will mean that Indigenous knowledges are equally heard and integrated in the provision of culturally safe care. This means decolonising our education systems so that psychologists receive an inclusive and broad education that enables them to work effectively. It also means addressing the underrepresentation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander psychologists.

The Australian Indigenous Psychology Education Project (AIPEP) is working to do exactly this. AIPEP aims to increase representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander psychologists and decolonise psychology through the integration of Indigenous psychology in higher education.

AIPEP has been working with more than 70% of higher education providers nationally to embed cultural responsiveness in psychology courses and support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander psychology students. Tremendous changes are already occurring, including demonstrated efforts by providers to decolonise curricula.

AIPA works closely with AIPEP and has played a vital role in representing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander psychologists on national boards and key stakeholder working groups. This has included recent collaborations with peak psychology bodies to address cultural responsiveness competencies of current and emerging psychologists, to improve cultural safety with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. We have also contributed to the historic Australian Psychological Society’s apology and its Black Lives Matter statement.

AIPA is proud to be involved in so many initiatives and to provide expertise on national matters that affect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander psychologists, our people, and communities. However, AIPA remains unfunded and relies on volunteer experts. AIPA is in urgent need of funding to continue to do this important work and to continue to be a national voice for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander psychologists.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander healing is a journey, and one that we walk together. Decolonising the mental health system is part of the journey to fairer representation and culturally safe care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. For this journey to be effective, we must work alongside and empower Aboriginal community controlled health services (ACCHS). Effective government partnerships and needs-based funding of these services are crucial to systemic changes in mental health.

• Crisis support services can be reached 24 hours a day: Lifeline 13 11 14; Suicide Call Back Service 1300 659 467; Kids Helpline 1800 55 1800; MensLine Australia 1300 78 99 78; Beyond Blue 1300 22 4636

• Vanessa Edwige is a Ngarabal woman, a registered psychologist, the chair of the Australian Indigenous Psychologists Association and a director on the board of the Aboriginal wellbeing and mental health leadership body Gayaa Dhuwi (Proud Spirit) Australia

• Dr Joanna Alexi is a research associate at the University of Western Australia’s School of Indigenous Studies and Poche Centre for Indigenous Health

• Belle Selkirk is research fellow at the University of Western Australia’s School of Indigenous Studies and Poche Centre for Indigenous Health

• Patricia Dudgeon is a professor at the University of Western Australia’s School of Indigenous Studies and Poche Centre for Indigenous Health